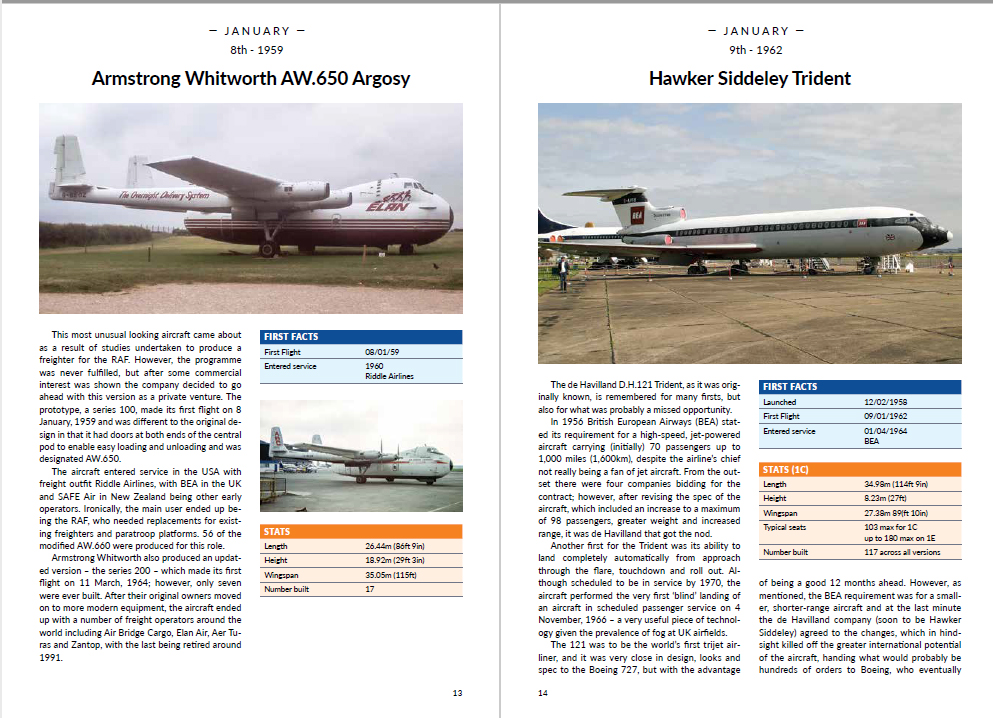

A guide to one of Britain’s most iconic, and undervalued airliners – the Hawker Siddeley Trident.

Origins

Hawker Siddeley Trident 1C, G-ARPK, at London Heathrow (Photo: Steve Fitzgerald, distributed under a GFDL 1.2 Licence)

In July 1956, British European Airways (BEA) issued a requirement for a jet airliner with more than two engines, which was capable of carrying up to 100 passengers in a high density layout at 520kts, operating from 6,000ft runways and able to achieve a range over 1,000 miles. Proposals were received from six companies which were later refined to three: the Avro 740, Bristol 200 and De Havilland DH.121. The following year, the government set conditions for the tender by encouraging various aircraft companies to merge into larger groups. As a result, De Havilland, Hunting and Fairey formed a consortium called AIRCO (Aircraft Manufacturing Company) and Bristol joined the Hawker Siddeley Group. Although the government favoured the Bristol-Hawker Siddeley project for its better financial backing, the Ministry of Transport gave BEA approval to negotiate their first order for the DH.121 in August 1958.

By this time the DH.121 project had developed into an aircraft with an overall length of 126ft 8in, wings of 107ft span swept at 35 degrees, a maximum weight of 123,000lbs and could accommodate up to 117 passengers. The proposed power-plant was three Rolls-Royce Medway engines, arranged with two on either side of the fuselage and the third at the base of the vertical stabiliser. However, in early 1959, BEA decided that the DH.121 design was too large for its requirements, preferring a substantially smaller and lighter aircraft with similar performance characteristics to the original DH.121, the decision being influenced by a sudden decline in air traffic growth. De Havilland revised the design of the DH.121, with the fuselage shortened by 13ft, the wingspan reduced by 17ft, a reduction in the gross weight to 105,000lbs and seating cut to a maximum of 96 passengers. In addition, the Medway engines were replaced by three, smaller Rolls-Royce Spey by-pass engines. In August 1959, BEA signed a contract for twenty-four DH.121 aircraft with an option for a further twelve. No prototypes were to be built. Towards the end of 1959 De Havilland became part of Hawker Siddeley and the AIRCO consortium was broken up. The DH.121 was named the Hawker Siddeley Trident 1C in September 1960.

The first Trident 1C (G-ARPA) made its maiden flight on 9 January 1962. By January 1963 there were four Tridents involved in the test programme which involved around 2,300 flying hours before a Certificate of Airworthiness was granted in February 1964. BEA received its first Trident 1C (G-ARPG) in the same month, and the aircraft entered service on 11 March 1964 on a flight from London Heathrow to Copenhagen.

General Features of the Trident

Hawker Siddeley Trident 2E, G-AVFM, of BEA (Photo: clipperarctic, distributed under a CC BY-SA 2.0 Licence)

The Trident had an all-metal construction with a T-tail and a low-mounted wing. The fitting of the engines at the rear of the fuselage allowed the wings to be lighter and more aerodynamically efficient. The Trident 1C had inboard Krueger flaps, leading edge droops and double-slotted trailing edge flaps. On all the other variants, the droops were replaced by leading-edge slats. The horizontal stabiliser with elevators was placed on top of the vertical stabiliser to avoid any efflux from the engines.

The undercarriage was an unusual feature of the Trident. The steerable twin nose-wheel was offset 24in to the left of the centreline and retracted sideways, creating a space below the flight deck for storage and control equipment. The main gear had four wheels on each unit, which rotated sideways through 90 degrees during retraction into the bottom of the fuselage.

A distinctive and unusual feature of the Trident at its inception in the early 1960s was the installation of a Bristol Siddeley Auxiliary Power Unit (APU) which gave the aircraft independence from external ground power sources. The APU was initially mounted in the belly, under the wing centre section. However, the heat generated led to problems with tarmac melting and fire and it was relocated to the base of the rudder above the centre engine exhaust.

Hawker Siddeley Trident 2E, B-280, of the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) (Photo: Lars Söderström, distributed under a CC BY-SA 3.0 Licence)

The Trident had a triplex safety system, with three hydraulic and three electrical systems, including three autopilots, each driven by an engine. The Trident was the first airliner designed specifically to have the eventual ability to land automatically, allowing it to operate into airports with zero decision height and zero visibility. The first stage in the development of this ‘Autoland’ ability was called ‘Autoflare’, which involved the autopilot performing the flare-out through automatic control of airspeed, throttles, pitch and thrust retard, while the pilot kept the aircraft lined up with the runway through the use of the ailerons. The Autoland system involved the autopilot coupling with an airport’s Instrument Landing System (ILS) for runway alignment and glide slope guidance, with the autopilot taking full control of the landing.

Trident Variants

Hawker Siddeley Trident 1C, G-ARPJ, at London Heathrow (Photo: Steve Fitzgerald, distributed under a GFDL 1.2 Licence)

Trident 1C: the first variant to be built, with a length of 114ft 9in (34.98m), wingspan of 89ft 10in (27.38m) and powered by three Rolls-Royce Spey 505 engines, each providing 10,410lb of thrust. The Trident 1C could accommodate 98-109 passengers, depending on the seating configuration, and had a range of 1,010nm (1,870km). Twenty-four 1C variants were built, all for BEA, although only 23 aircraft were delivered with one aircraft crashing during a test flight.

Hawker Siddeley Trident 1E, YI-AEB, of Iraqi Airways (Photo: RuthAS, distributed under a CC BY 3.0 Licence)

Trident 1E: an improved Trident 1C primarily developed for the export market and especially for operations from hot and high airfields. It had the same fuselage length as the 1C but a 5ft 2in longer wing span which increased the wing area by 6.5%. The leading-edge droops on the wings of the 1C were replaced by leading-edge slats. The Trident 1E had up-rated Rolls-Royce Spey 511 engines, giving a thrust of 11,400lb, and greater fuel storage capacity achieved by increasing the size of the centre fuselage fuel tank, leading to an improved range of up to 1,910nm (3,540km). The maximum seating capacity of the 1E was139, in a six-abreast configuration. A total of 15 1E variants were built, with initial operators including Pakistan International Airlines (4), Kuwait Airways (3), Iraqi Airways (3), Channel Airways (2), Northeast Airlines (2), and Air Ceylon (1).

Hawker Siddeley Trident 2E, G-AVFB, on lease to Cyprus Airways from BEA (Photo: Ralf Manteufel, distributed under a GFDL 1.2 Licence)

Trident 2E: The 2E variant was developed specifically for BEA following a request for a longer range version of the Trident (E is for Extended Range). It featured an aerodynamically refined wing, through the fitting of Kuechemann wing tips which extended the wingspan by 3ft (0.9m) to 98ft (29.9m). The variant was fitted with more powerful Rolls-Royce Spey 512 engines, with 11,960lb thrust from each engine. An additional 350 gallon fuel tank in the vertical stabiliser resulted in a range, with a maximum passenger load, of 2,200nm (4,075km), increasing to 2,550nm (4,720km) with ninety passengers. Fifty Trident 2Es were produced, the most of any Trident variant, and they were delivered to BEA (15), Cyprus Airways (2) and the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) (33).

Hawker Siddeley Trident 3B, G-AWZG, of British Airways (Photo: Michel Gilliand, distributed under a GFDL 1.2 Licence)

Trident 3B: Hawker Siddeley developed the Trident 3B in response to BEA’s request for a larger aircraft. However, BEA only agreed to a larger Trident following financial support from the government for the development of a stretched Trident. The fuselage of the 3B variant was lengthened by 16ft 5in (5m), 8ft 5in forward and 8ft aft of the wing, through the insertion of three plugs into a 2E fuselage, creating an increased capacity of up to 180 passengers in an all-economy seating configuration. Modifications were made to the wing to increase the angle of incidence, provide a wider chord and increase the area of the trailing-edge flaps. The engines remained the same as the Trident 2E variant (Rolls-Royce Spey 512) so, in order to provide additional power for this much heavier aircraft, a Rolls-Royce RB162 booster engine was fitted where the APU had previously been installed, above the centre engine exhaust. The booster engine provided an additional 5,230lb thrust for take-off and climb, which was particularly important when operating from hot and high locations. The APU was relocated to the front of the vertical stabiliser. The range of the 3B was 1300nm (2408km). Twenty-six Trident 3Bs were built, all initially delivered to BEA.

Trident Super 3B: CAAC ordered two extended range Super 3Bs in November 1972, the only two aircraft of the type to be produced. The variant was the same as the 3B apart from additional fuel capacity which increased the range to 1,825nm (3,380km) at maximum payload.

Technical Specifications

Hawker Siddeley Trident 1E, G-AVYC, of Northeast Airlines (Photo: Steve Fitzgerald, distributed under a GFDL 1.2 Licence)

| VARIANTS | ||||

| 1C | 1E | 2E | 3B | |

| Length | 114ft 9in (34.98m) | 114ft 9in (34.98m) | 114ft 9in (34.98m) | 131ft 2in (39.98m) |

| Wingspan | 89ft 10in (27.38m) | 95ft (28.96m) | 98ft (29.87m) | 98ft (29.87m) |

| Wing area | 1,358 ft2 (126.2m2) | 1,415ft2 (131.5m2) | 1,462ft2 (135.8m2) | 1,462ft2 (135.8m2) |

| Max Take-off Weight | 115,000lb (52,163kg) | 128,000lb (58,060kg) | 142,500lb (64,637kg) | 150,000lb (68,039kg) |

| Engines | 3 x Rolls-Royce Spey 505 | 3 x Rolls-Royce Spey 511 | 3 x Rolls-Royce Spey 512 | 3 x Rolls-Royce Spey 512 + 1 x Rolls-Royce RB162 |

| Thrust | 3 x 10,410lb | 3 x 11,400lb | 3 x 11,960lb | 3 x 11,960lb + 5,230lb |

| Fuel capacity | 22,000L | 24,700L | 26,250L | 24,200L |

Preserved Tridents in the UK

There are three complete Tridents currently on display in the UK:

Trident 1C G-ARPO under restoration at Sunderland.

Trident 1C, G-ARPO (c/n: 2116), operated by BEA and British Airways between January 1965 and March 1983, is at the North East Land, Sea and Air Museums, Sunderland (https://www.savethetrident.co.uk/)

Hawker Siddeley Trident 2E, G-AVFB, on display at the Imperial War Museum Duxford (Photo: Nigel Richardson)

Trident 2E, G-AVFB (c/n: 2141), operated by BEA, Cyprus Airways and British Airways between May 1968 and March 1982, is part of the British Airliner Collection at the Imperial War Museum Duxford, Cambridgeshire (https://www.iwm.org.uk/visits/iwm-duxford)

Hawker Siddeley Trident 3B, G-AWZK, on display at the Runway Visitor Park, Manchester Airport. (Photo: Craig Sunter, distributed under a CC BY 2.0 Licence)

Trident 3B, G-AWZK (c/n: 312), operated by BEA and British Airways between October 1971 and November 1985, is at the Runway Visitor Park, adjacent to Manchester Airport (https://www.runwayvisitorpark.co.uk/)

Flying Firsts

Learn more about the Trident and its variants, as well as many other airliner types in Flying Firsts – our full colour airliner reference guide, packed full of information like dates, facts, data, as well as descriptive histories and photographs.

Find Out More

2 comments

Hi Matt, its a real pity the Science Museum at Wroughton airfield is not open to the public, as they have some important and interesting airliners there, including Trident 3 G-AWZM.

I believe you have been there ?

Hi Merv, yes I’ve visited it once and got close to G-AWZM. It is a shame it’s not open, but I believe there are plans to make it available through a new visitor centre in the future.

Matt