Syed Hassaan Khalid continues his series of articles looking at the world’s most notable aviation disasters and incidents.

In this episode he looks at the “fatal approach” of Pakistan International flight 268 at Kathmandu on 28 September 1992.

Read Episode 1 looking at the Tenerife Airport Disaster of 1977.

Read Episode 2 looking at the Helios 522 disaster in 2005.

Read Episode 3 looking at the Germanwings 9525 disaster in 2015.

Prologue – Pakistan International PIA268

“Cleared for finals… Runway 02”. These were the last words from the pilots of flight 268, which crashed moments after receiving clearance for the final approach, just 10 miles prior to touchdown at Kathmandu.

Let’s have a look at what went wrong on this scheduled passenger flight from Karachi.

The Incident

Creative Commons: Coolgenx1

On a routine morning at Karachi’s Jinnah International Airport (KHI/OPKC), Pakistan International Airlines flight 268 takes off at 11 am local time and heads towards the northeast. This is a scheduled passenger flight carrying 155 souls, bound for Nepal’s capital Kathmandu; located around 1,400m above sea level.

Today’s flight is operated by an Airbus A300, registered as AP-BCP, which was previously operated by EgyptAir, Kuwait Airways, Capitol Air, Air Jamaica, and Condor.

As the flight is in the final phase, the flight captain, Iftikhar Janjua (6,200 hrs on the A300) along with first officer Hassan Akhtar (1,500 hrs on this aircraft type) are discussing the approach pattern and the weather. Among the flight crew, there are two flight engineers, who have almost 7,000 hours on the A300, altogether.

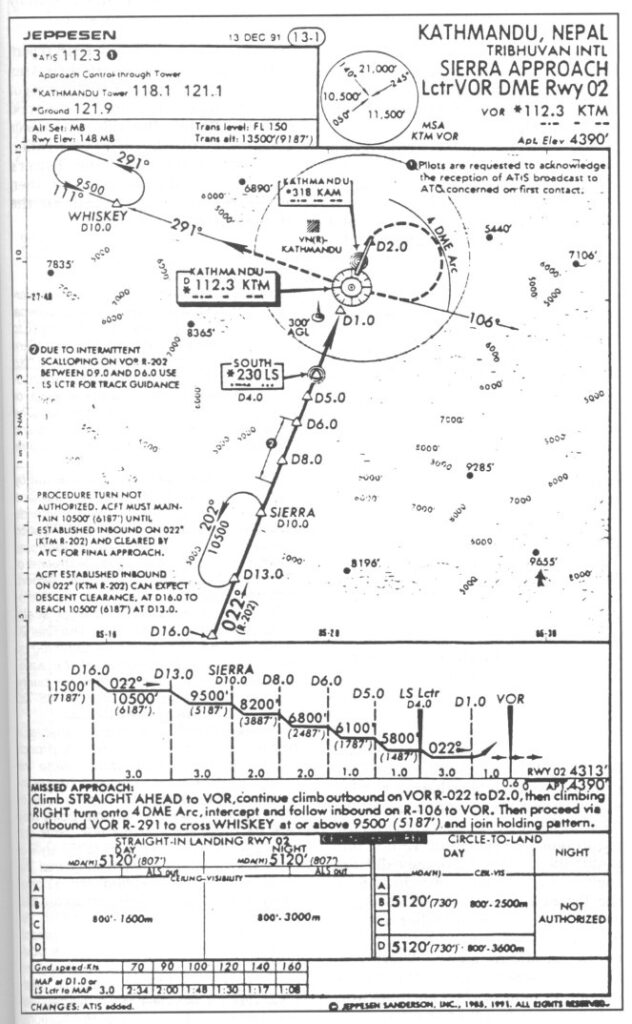

Shortly, Kathmandu’s ATC tower conveys the pilots to expect the Sierra approach which is a challenging arrival divided into seven steps. It requires descending to a certain altitude at different levels to successfully avoid the Himalaya mountains.

The captain hands over the approach chart to the first officer, who attaches it to the clipboard. They began their final approach after being cleared by the tower. The first officer reports initiating a descent towards Kathmandu, at 11,500ft, and around 16 miles from touchdown. The ATC asks the aircraft to report the next position when 10 miles from the runway.

As the aircraft nears the 10-mile mark, F.O Hassan reports the altitude to be 8,200ft. In response, the ATC further give clearance for the next reporting point at 4 miles, and unfortunately, this was the last conversation between the pilots and the ATC.

The assigned controller waits for the aircraft to reach the specified mark. As time goes by, the controller becomes suspicious and contacts flight 268 to report their position, but no response is heard. The controller makes several attempts to establish contact, but only silence is observed from the aircraft.

Not long after the last contact with the aircraft, the flight hit the rapidly approaching mountains and erupted into flames. It had almost 18,000 kg of fuel left in its tanks.

The crash site is located by the Nepalese military. Upon reaching, as they analyze the situation, the hopes of finding any survivors are very narrow.

The Investigation

Soon after the crash, the military and the investigators arrived at the crash site near the Bhattedanda village, situated in the Bagmati municipality in Nepal, to collect the pieces of evidence and the cockpit instruments including the black box for the investigation.

This crash happened just two months after the crash of Thai Airways flight 311 in the same region, operated by an Airbus A310. This became a baffling mystery for the local investigators, as the two aircraft were believed to have crashed the same way. Thus, the Nepalese government asked for assistance from the UK’s AAIB (Air Accident Investigation Branch).

In a matter of hours, Andrew Robinson, a lead investigator from the AAIB reaches Nepal to accelerate the investigation process. He examines the wreckage distribution from various angles.

Due to the uneven terrain, the investigators faced great difficulty in reaching the crash site. However, the only recognizable component of the aircraft was the tail, resting on the base of a mountain in a forest. After spending a few hours on the crash site, the investigators were assured that collecting and examining the wreckage was an extremely complex task, as the slopes made it nearly impossible to plod around the area. The situation confirmed that there were no survivors, and all 158 passengers are presumed dead.

The complement included 94 Europeans, 30 nationals of Pakistan and Nepal, 4 from Bangladesh, and 3 U.S citizens.

The first thing the investigators find out was the aircraft’s position. It crashed just a mile after reporting the altitude, approximately 9 miles from the assigned runway. Furthermore, the flaps were deployed and the aircraft was not pitching down, which eradicated the possibility of a loss of control. One after the other, the investigators continued ruling out the possibility of any mechanical failure.

Descend altitudes Sierra Approach

The next point that the officials focused on was the misinterpretation of the approach procedure. As it was a complex and unique procedure, the pilots may have decided to opt for a visual approach. However, this remained on agenda for a short time, as the visual approach was nearly impossible with thick and almost 100% cloud cover, making it at another dead end.

As the Sierra approach charts were taken into consideration and compared with the altitude graph of flight 268, there came an unexpected and shocking twist. The pilot-in-command had set the correct heading but unfortunately was one step ahead of the required flight level (i.e., the altitude was 1,000ft lower on each stage in accordance with the chart). They got the breakthrough, but why and how did they end up reading the charts incorrectly?

The investigators noticed that there are just two points where the pilots could have clipped their charts, and both made it nearly impossible to read them from the seat.

However, the only possible explanation for the misinterpretation of the charts was the complexity and a hypothesis that the captain’s thumb came over the first step of the chart, hence, the approach was started from 10,500ft instead of 11,500ft. Similarly, the F.O. reported their current altitude from the chart without double-checking with the altimeter that they were 1,000ft lower.

Conclusion

Final approach to Kathmandu -Wikimedia commons – Siecinski

The final theory that the investigation team presented was actually the negligence of the flight crew’s in-flight resource management.

A series of errors, initiated from the incorrect judgment of the Sierra approach, then reporting their current altitude from the chart instead of the altimeter, and the placement of the approach chart on the instrument panel instead of the controller/yoke.

The investigation board recommended the Kathmandu ATC install radars for tracking aircraft and making the Sierra approach less complex. They further suggested PIA install clips for mounting charts on the yokes of its Airbus A300s and A310s.

A memorial is set up at the base of the mountain where the crash occurred, known as Lele Park. Many Pakistani and European tourists visit this place, especially on September 28 each year.